One of my main goals for Hamacon analog gaming was running events. This is typical when you’re talking about CCGs (tournaments) or RPGs (one-shot adventures), but I wanted to extend this to board games. Specifically, I wanted to introduce games that were fun or interesting, weren’t necessarily popular (i.e., you wouldn’t find on Tabletop or similar shows), and weren’t necessarily easy to learn (i.e., not Cards Against Humanity or Love Letter).

This is an idea I stole from Momocon, mainly because I enjoy it. When I do board gaming at a con, it’s because I want to try new games. Scheduled “learn to play” demos are great–you don’t have to form a group before you go in, and you don’t have to spend time read the rules. You’re getting an intro from someone who loves the game enough to demo it.

When you’re considering building an analog gaming schedule, there’s a few things you need to think about:

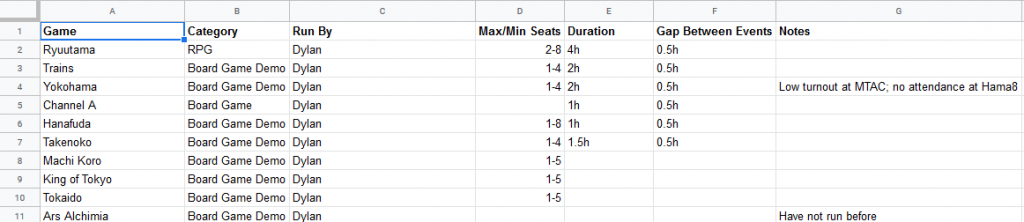

Event submission. When I’m scheduling gaming events, I like to make sure I collect the following information to put in the schedule and/or descriptions:

- Estimated duration. I err on the side of longer if there’s any chance of the game running long. You want to respect attendees’ time at a convention, and one way to do that is to communicate how much time they’re committing when they play your game. (I also keep a note of “gap between events” so that gamemasters have overflow/downtime.)

- Maximum number of players. This is essential for creating sign-in sheets. I also include it in the game description for the schedule, since as a player I’d like to know. (However, I’ve wondered if this can backfire–would people write off an event that could only hold 4 people, assuming it would fill up quickly?)

- Format and cost (for CCG tournaments): Make it clear what they’re getting into (and what kind of deck they need to bring), and what it will cost. This also helps flag submitters that intend to sell products or collect money, just in case you need to route them to other con staff for that.

- Level and allowed options (for RPGs): If players have the option of bringing their own character, make sure they know exactly what’s required so they won’t have to do any work during the session.

- Equipment provided for players: For example, pre-generated characters, dice, or miniatures. Most attendees likely won’t be prepared with characters, books, or dice, so this lets them know the event is still open to them.

- Setup. Make sure you know if the event is a table for board games or RPGs, for miniatures (which may require a larger table, or a combination of tables), or for social games like Werewolf (which may not even require a table).

- Time slot: If someone else is submitting an event, make sure you know when they’re available and not otherwise occupied.

Scheduling. Unless you’re at a gaming convention, the analog gaming area at a con is probably not the primary draw. Its traffic is usually dependent on what else is (or, rather, is not) going on, mainly because it’s slower and gaming events don’t neatly fit into 1-hour blocks.

- Don’t schedule games for the first hour or so the con is open. In my experience, analog gaming was dead for the first few hours. This isn’t a time-of-day thing; it was often as dead at 12:30pm on Friday as it was at 10:30am on Saturday. Analog gaming doesn’t tend to be the first place people stop–you want to see what’s going on before committing a couple of hours to a game. Once you get one game going, it tends to fill up fast.

- Don’t schedule games against the rave, or whatever big evening event your con has. It’s going to drastically reduce traffic to other areas of the con, and people not interested in the big event will probably leave.

- Avoid scheduling games during busy hours if table space might be an issue. In my experience, this was early-to-mid afternoon–late enough that everyone’s gotten to the con, but early enough that the big events haven’t happened yet. If analog gaming was going to fill up, that’s when it would happen, which means I’d have to kick people off a table to set up a game.

Game choice. Just because you like a game does not mean anyone will show up to play it. I scheduled quite a few games for the hypothetical hardcore Eurogamer who likes learning new games (i.e., me) that never happened.

- Don’t get discouraged. Unless you’re at a massive convention, it’s inevitable that a game session will go empty. Maybe it’s for a favorite game, which stings. Personally, I have a hard time thinking I made a dumb choice when I decided to schedule games.

It’s ok. Tabletop gaming is an odd beast, so your choices will always be speculative. Focus on the sessions that did get interest–because odds are someone in that group discovered something new they really enjoyed. - Theme matters. I tried for years to get a Trains or Yokohama demo to happen, because they’re games that do some really neat things, but don’t have name recognition. (Also, I try to highlight games from Japan at anime cons). At Hamacon, no one showed up, and they were only lightly attended when I ran learn-to-plays at MTAC.

However, I had a full table for a learn-to-play for Bob Ross: Art of Chill this year, and Takenoko learn-to-plays always did really well. In some ways they’re crunchier and heavier than Trains, but they also have well-known and/or friendly themes. - Name recognition matters. D&D is going to do better than Ryuutama or Golden Sky Stories, because people know what it is. Should you still run those games? Absolutely, if one of your goals is to help people discover something new. But know that they’re speculative, and don’t fixate too hard on those games.

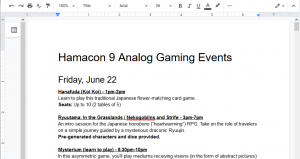

- Provide descriptions, and set up games beforehand. If you read board game reviews or browse online game stores, chances are there are a lot of games that you recognize and vaguely know about. But many people don’t, so giving them a chance to tie a picture or an explanation to a name is helpful.

Planning. I typically plan the schedule using a three-step process:

- Brainstorming: In this phase, I track a list of possible games, including all of the details in “Event Submission” above, in a new Google Sheets document. I also track general category (CCG, RPG, learn-to-play, etc.) Anything I have the slightest inkling of running goes here; any submissions from others go on the list as well.

It’s helpful to create a summary table to the side that shows a total count of hours per gamemaster (compared to total hours in the con). That way, you can ensure you’re not overbooking yourself or others as you plan.

- Schedule Grid: Here’s where things get real and choices are made. In a separate tab of the document, I start building out the actual grid. This is also what I pass off to be printed in the schedule, so niceties like color-coding and borders matter.

- Event Descriptions: This stage occurs in a separate Google Doc. It’s where I add all the details that might be included in a guide or detailed signage. (I add all of these descriptions in my “Hamacon Analog Gaming Bible” document so that I can reuse them year-to-year.)

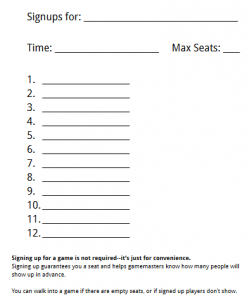

Sign-ups. At Hamacon, I always had sign-up sheets for each scheduled game, whether it’s something popular like D&D or something more speculative like a Hanafuda learn-to-play.

I organize my sign-up sheets into a three-ring binder with tabs for each day. Each sheet clearly labels the game, time, and maximum number of seats. I also have an explanation that sign-ups are a convenience and not required, but I still get questions about the process.

On the other hand, Momocon doesn’t do this for their learn-to-play sessions, and I can understand why. I won’t argue whether you should or shouldn’t.

Here’s the reasons I did it:

- It’s always nice to know what’s getting a response and what isn’t. I can sometimes tell ahead of time whether a game will be popular, or whether no one will show up. Of course, this isn’t always accurate–you’ll have people show up last-minute to games no one’s asked about, or no-shows to games that have a full sign-up sheet.

- It resolves some issues with first-come, first-served. If multiple people ask about a game throughout the day, they can reserve a spot (or get on the waitlist). There’s less of a chance they’ll plan their schedule around the game only to be disappointed that it’s full.

It also gives me a feel for whether I should wait for a few minutes for other players to arrive. - Stats. After each scheduled game, I write the number of attendees on the sign-up sheet and drop it in my “checked in” box. As with tracking check-outs, I don’t have any magic data that will tell you exactly what works, but it’s nice to refer to previous years when building schedules.

Here’s the downsides to offering signups for:

- It can be a hassle. I ran maybe 3-5 games a day at Hamacon, so it was easy to manage the sign-up sheets. For a larger convention, that would be a much larger book.

- Often, people who signed up won’t show. Usually this isn’t a problem, but popular events might appear full (which turns people away), only to end up with extra space. Creating a waitlist can help, but it’s still discouraging.